Naacl2021

Published:

Here are the summary of some of talks from NAACL 2021. So far, I only summarized the following papers, I will be summarizing more. So, I will either append it here or a new blog post. Feel free to check back soon.

Table of Contents

- Video-aided Unsupervised Grammar Induction

- Unifying Cross-Lingual Semantic Role Labeling with Heterogeneous Linguistic Resources

- It’s Not Just Size That Matters: Small Language Models Are Also Few-Shot Learners

- Learning How to Ask: Querying LMs with Mixtures of Soft Prompts

- How many data points is a prompt worth?

- Contextual Domain Classification with Temporal Representations

Video-aided Unsupervised Grammar Induction

By Songyang Zhang, Linfeng Song, Lifeng Jin, Kun Xu, Dong Yu and Jiebo Luo

Best Long Paper

Grammar induction aims to capture syntactic information in sentences in the form of constituency parsing trees. Sup

Unsupervised grammar induction provide evidence for statistical learning because it has minimal assumption about linguistic knowledge built into the models

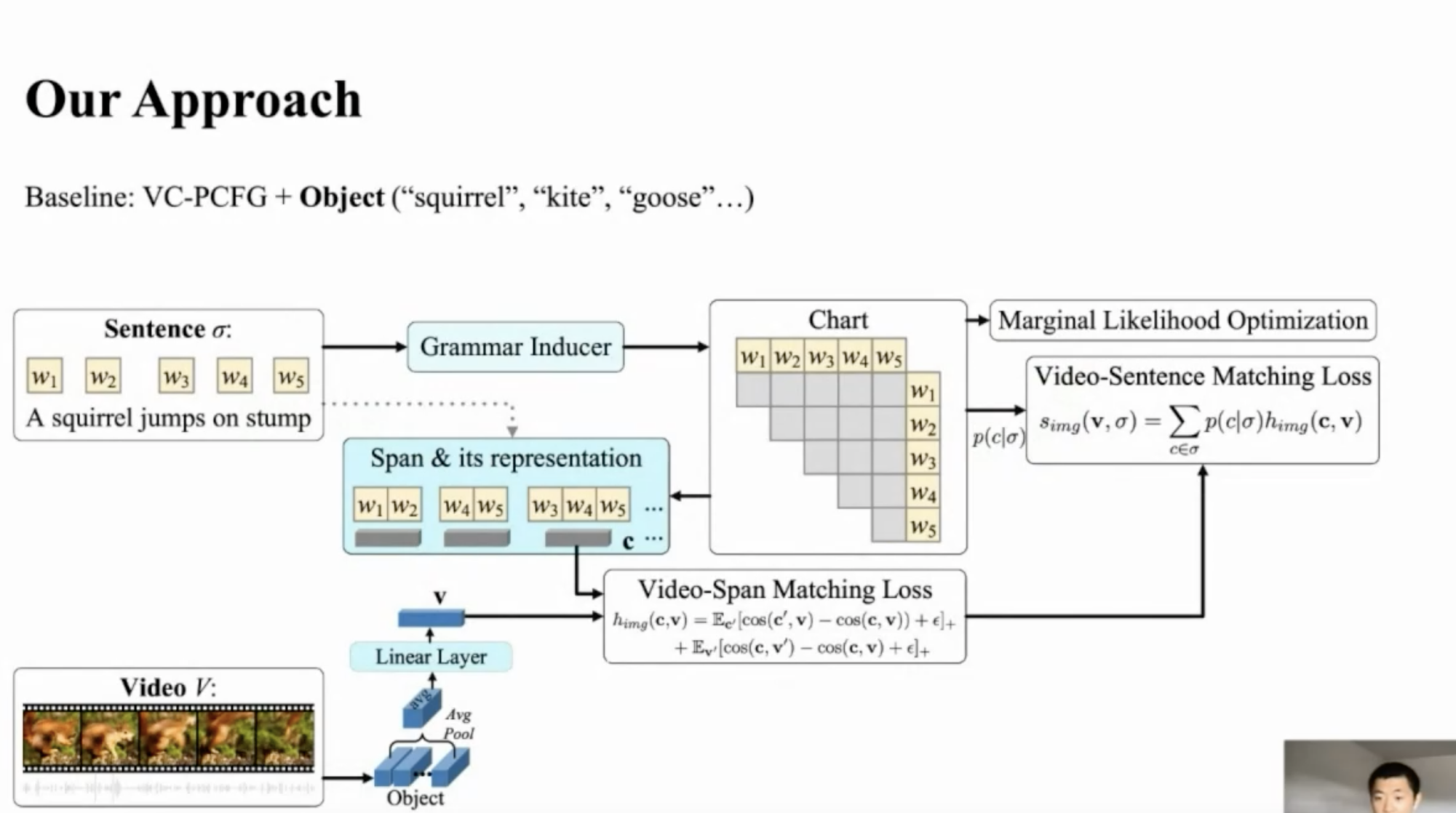

There are many texts and videos/images on social media and images have shown to help us induce syntax structure. In Image0-aided unsupervised Grammar induction, the model exploits regularities between text spans and images. Videos not only represent static objects, but they can also show actions and dynamic interaction between objects and can represent verb phrases.

The paper is inspired by Compound PCFG in which a grammar inducer is used to create the chart and then they optimize on marginal likelihood of the sentence. Visually Grounded-PCFG, consider image sentence matching during the training. However, simply replacing images with videos is not trivial due to multimodality and temporal modeling in videos.

Image taken from the presentation

The baseline model created by the authors combines VC-PCFG with objects. The authors also compare this baseline with VC-PCFG + [Action, scene, audio, OCR, Face, speech]. In the final model, all the aforementioned features from a Multi-Modal Transformer are extracted and used. In the paper, it’s been shown that this model (MMC-PCFG) outperforms all the other baselines consistently on three different datasets.

Unifying Cross-Lingual Semantic Role Labeling with Heterogeneous Linguistic Resources

By Simone Conia, Andrea Bacciu and Roberto Navigli

Outstanding Long Paper

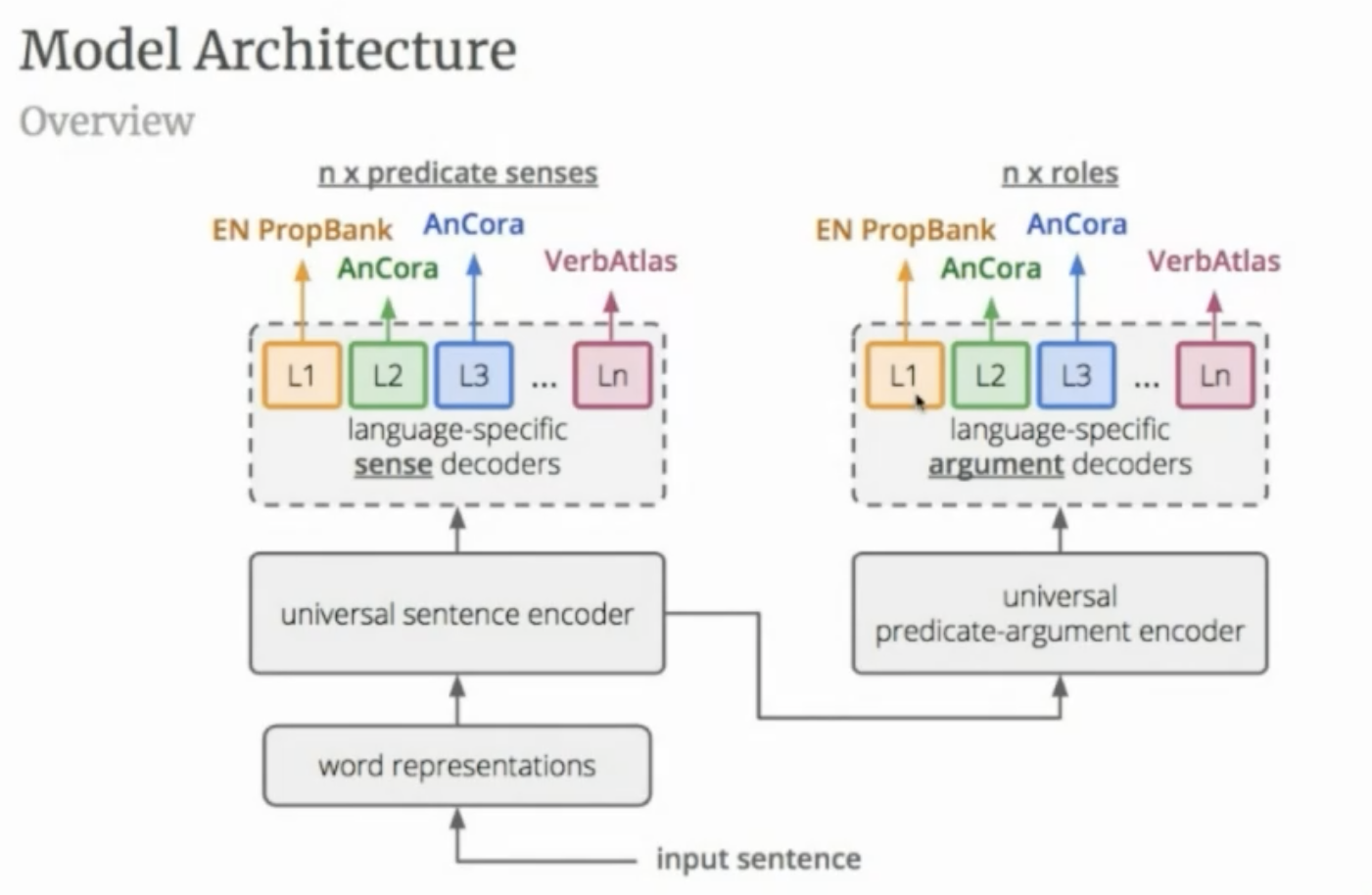

Semantic role labeling (SRL) is the task of automatically addressing “who did what to whom, where, when, and how?” SRL includes predicate identification and disambiguation, argument identification, and argument classification. SRL predicate-argument structure inventories are language-specific and simultaneously label semantics across languages is expensive and needs human experts (in the desired languages). Hence, there is a need for heterogeneous linguistic resources. The intuition behind this idea is that semantic relations may be deeply rooted beyond language-specific realization and as a result authors try to build a model that can learn from many inventories for deeper sentence-level semantics.

The model architecture (illustrated below) can be roughly divided into the following components: • A universal sentence encoder whose parameters are shared across languages and which produces word encodings that capture predicate-related information • A universal predicate-argument encoder whose parameters are also shared across languages and which models predicate-argument relations • A set of language-specific decoders which indicate whether words are predicates, select the most appropriate sense for each predicate, and assign a semantic role to every predicate-argument couple, according to several different SRL inventories

Image taken from the presentation

It’s Not Just Size That Matters: Small Language Models Are Also Few-Shot Learners

By Timo Schick and Hinrich Schütze

Outstanding Long Paper

In GPT-3 priming, the model is given a few demonstrations of inputs and corresponding outputs as context for its predictions, but no gradient updates are performed. Using priming, GPT-3 has shown that it has amazing few-shot abilities. However, the problem with priming is that we need gigantic language models, also priming does not scale to more than a few examples as the context window is limited to a few hundred tokens.

An alternative approach is pattern-exploiting training (PET) which combines the idea of reformulating tasks as cloze questions with regular gradient-based finetuning. More formally, the task of mapping inputs x ∈ X to outputs y ∈ Y , for which PET requires a set of pattern-verbalizer pairs (PVPs). Each PVP p = (P, v) consists of • a pattern P : X → T∗ that maps inputs to cloze questions containing a single mask; • a verbalizer v : Y → T that maps each output to a single token representing its task-specific meaning in the pattern

By adopting PET, the authors showed that even a small model such as ALBERT can outperform GPT-3 on SuperGLUE. Through a series of ablation studies, authors showed that pattern and verbalizers significantly contribute to the performance of the model. From the paper, one can conclude that PET works well with small language models, and scaled to more examples than fit into the context window. However, the disadvantage of PET compared to few-shot learning is that PET requires fine-tuning multiple models for each task and doesn’t work for generative tasks.

Learning How to Ask: Querying LMs with Mixtures of Soft Prompts

By Guanghui Qin and Jason Eisner

Best Short Paper

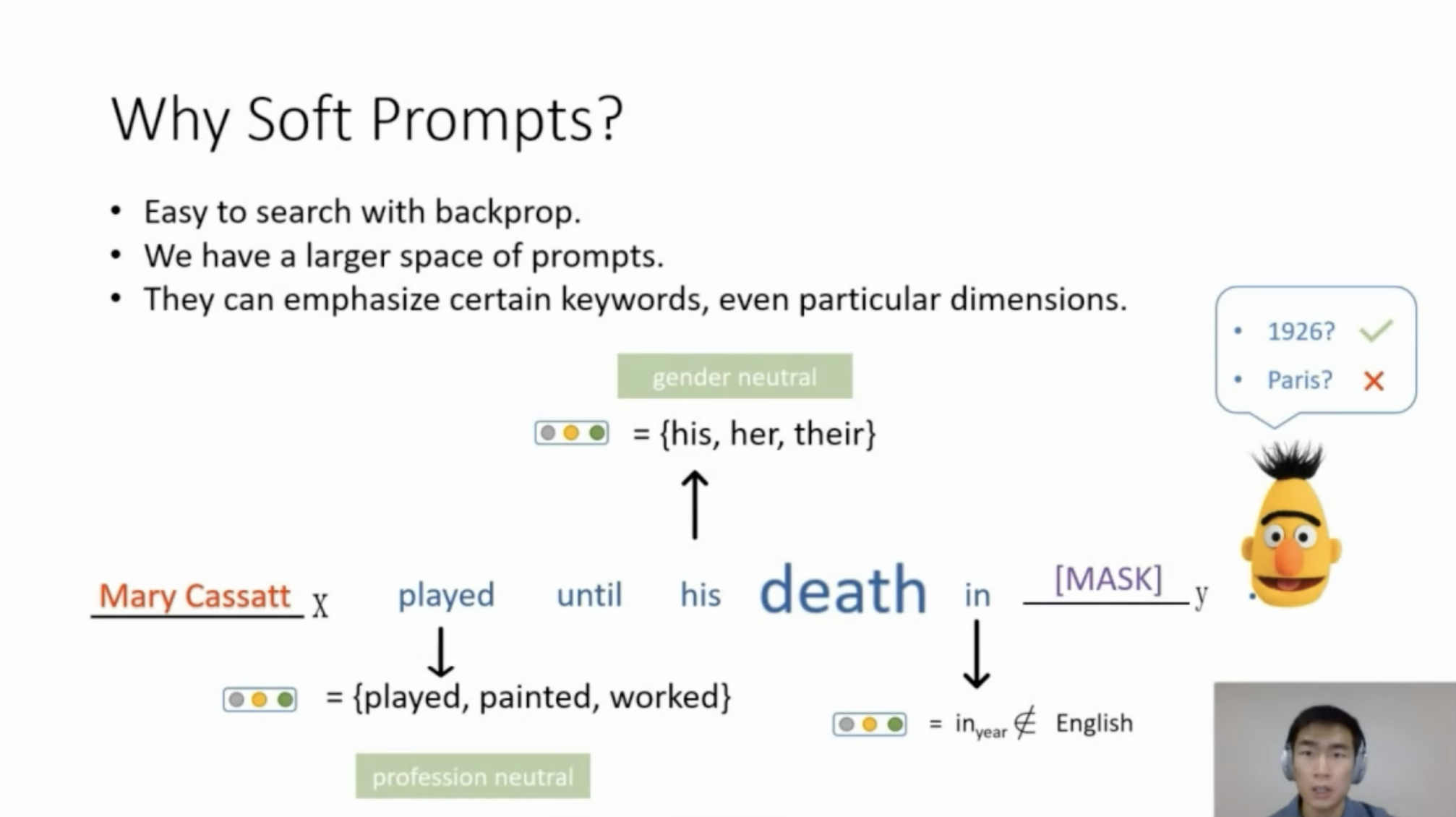

In few shot settings, we can extract factual knowledge from the model’s training corpora by prompting the model. In this paper, the authors show that the choice of prompt is important for the performance of the model and explore the idea of learning prompts by gradient descent—either fine-tuning prompts taken from previous work, or starting from random initialization. This can easily be achieved since from the perspective of LM words are just continuous vectors. Hence the used prompts consist of “soft words,” i.e., continuous vectors that do not necessarily word type embeddings from the language model. This is called soft prompts and the benefit of using the soft prompts (compared to hard prompts and words) is that they are easy to search with backprop and they enable us with a larger space of prompts.

In addition to soft promoting, for each task, authors optimize a mixture of prompts, learning which prompts are most effective and how to ensemble them. They show that across multiple English LMs and tasks, their approach hugely outperforms previous methods, showing that the implicit factual knowledge in language models was previously underestimated. Moreover, this knowledge is cheap to elicit: random initialization is nearly as good as informed initialization.

Image taken from the presentation

How many data points is a prompt worth?

By Teven Le Scao and Alexander Rush

Outstanding Short Paper

When fine-tuning pre-trained models for classification, researchers either use a generic model head or a task-specific prompt for prediction. In this paper, authors compare prompted and head-based fine-tuning in equal conditions across many tasks and data sizes. They show that prompting is often worth 100s of data points on average across classification tasks.

To compare heads vs prompts, they consider two transfer learning settings for text classification: head-based, where a generic head layer takes in pretrained representations to predict an output class; prompt-based, where a task-specific pattern string is designed to coax the model into producing a textual output corresponding to a given class. Both can be utilized for fine-tuning with supervised training data but prompts further allow the user to customize patterns to help the model.

For the prompt model, we follow the notation from PET (described earlier here) and decompose a prompt into a pattern and a verbalizer. The pattern turns the input text into a cloze task, i.e. a sequence with a masked token or tokens that need to be filled.In order to measure the effectiveness of promoting, authors introduce a metric, the average data advantage.

Contextual Domain Classification with Temporal Representations

Tzu-Hsiang Lin, Yipeng Shi, Chentao Ye, Yang Fan, Weitong Ruan, Emre Barut, Wael Hamza, Chengwei Su

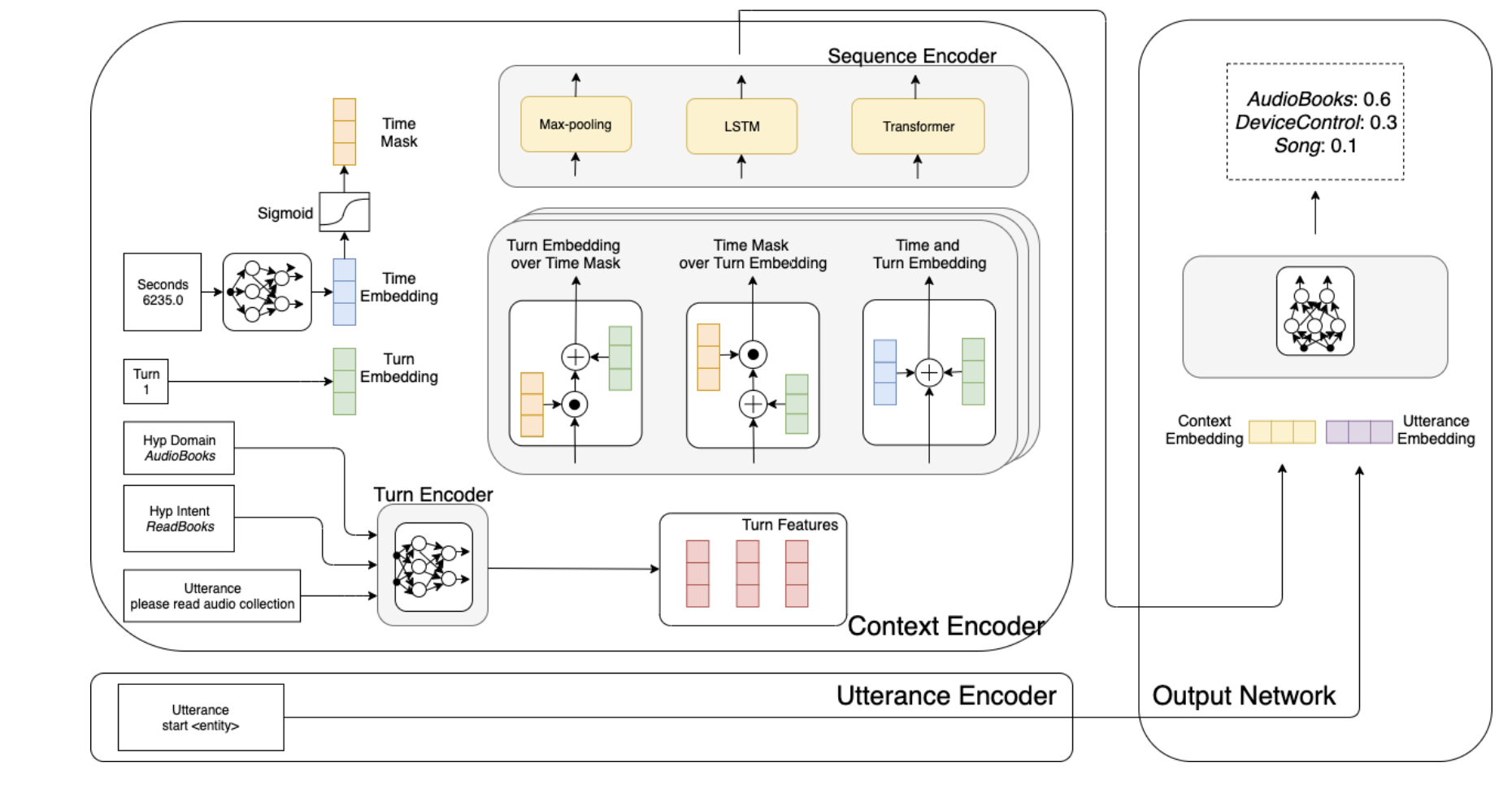

There are many domains in dialogue systems and defending on the domain, the concept of concept can vary from minutes to hours. This paper uses temporal representations that combine second difference and turn order offset information has been used to utilize both recent and distant context in various encoder architectures. More specifically, previous 9 turns of context within a few days have been included in the model. In order to determine which temporal information (turn vs time difference) contribute to the model, authors considered using time mask, turn embedding, turn embedding over time mask, time mask over turn embedding, and time and turn embedding. The model is shown below.

Image taken from the paper

Time mask feeds the time difference into a 2 layer network and sigmoid function to produce a masking vector. Turn embedding is the turn difference which is projected into a fixed-size embedding vector. Turn embedding over time mask provides turn order information on top of seconds (assuming turn is more important) and similarly in mask over turn embedding provides time seconds information on top of order turn (assuming time is more important). Finally, time and turn